Graffiti’s journey from Philadelphia to New York City

October 20, 2015

Graffiti, the subculture that seemingly blurs the line between vandalism and art, has a relatively short history despite the fact that people have been writing messages and creating illustrations in public places since ancient times. Of course, this was before such an act could be labeled as a subculture and centuries before it became popular to write your name (or tag) in a public place. There is some sense that graffiti must be defined and classified in order to analyze its history more appropriately.

However, this particular subculture often eludes a definition. Traditionally, it refers to writings or drawings that have been scratched, etched, painted or written in public places. I would make one modification to this definition—graffiti is almost always meant to be permanent, with writers or artists solidifying themselves in that particular area. Therefore, I wouldn’t classify someone who uses chalk in a public square as a graffiti artist since chalk is destined to wash off with the rain, and there is no intent for permanence.

It wasn’t until people started writing their names or tags in Philadelphia in 1970 that graffiti became about having an individual and personalized marking to reflect where they had been. Artists like Cornbread and Tracy 168 were the first to practice this method of simply writing their name or pseudonym in a public place. These artists would write their names anywhere they could—in public places, on train cars, or even on structures adjacent to highways, using aerosol cans or markers.

Graffiti’s proliferation to New York City is largely attributed to deliberate efforts on the part of these Philadelphia graffiti writers. However, this may have been a natural development, too. When this practice became popular in New York City in the early 1970s, there was competition to “get up” or write the most, so that as many people as possible could see your tag. If your tag was widespread or unique enough to stand out, the prize was fame. For this reason, graffiti writers began writing (or spraying) their tags on subway cars with markers or aerosol paint cans. That way, their work could be carried and seen across the city. This proved to be an easy task, as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority did not have sufficient security at the time to prevent this because subway tagging was a brand new trend.

The primary goal for most writers in the early 1970s was recognition, fame or notoriety, and this is obvious when one considers that most writers would simply write their first name accompanied by their street number address. The aforementioned Tracy 168 abided by this schema, as did many others. Inter-borough competition emerged as writers became aware of the tags of others, thus inspiring countless pieces in addition to rivalries between writers.

As the practice proliferated, however, graffiti writers would add illustrations or implement distinct styles apart from the bubble letters that were commonplace. The result was polka dots, crosshairs or other designs usually located within the characters. The practice of adding these designs quickly became attached to the subculture in the late 1970s. Writers were well aware that the possibilities were limitless, and they implemented new techniques as time went on. Tagging was just one form of graffiti as many began to practice “bombing,” in which the design is sacrificed for speed so as to avoid getting caught. This can also be referred to as a “throw-up.” An intelligent writer would make sure there were as few lines as possible in his work.

The idea behind this method was to use as few lines and colors as possible to write your tag, so as to create the work quickly without detection. Using fewer lines meant not having to cease spraying to begin a new line. Each second matters when you’re defacing public property.

Another method of graffiti is piecing, in which one takes a long time on a work in order to make the name aesthetically pleasing with a variety of colors. Piecing can only be done in places where there is little to no security, as writers need a significant amount of time to do a piece. The image that is later identified as “wildstyle” is a good example of a “piece.”

As the trend spread to New York City, distinct styles emerged in upper Manhattan and Brooklyn, but quickly merged together forming what is now referred to as wildstyle. Wildstyle is a term coined by one of the earliest writers, Tracy 168. Wildstyle is now common, and if you’ve seen any graffiti then you’ve probably seen this style, although it is hard to define because there are many variations.

It is sometimes very difficult to even read it despite it being incredibly distinct. It stands out using sharp, wildly complex edges along with characters in close proximity to one another. Much of wildstyle implements a significant degree of flair in the design too. Flair is anything other than the characters that helps the piece stand out, like the red droplet-looking things in the piece below.

Other styles emerged elsewhere, like the national birthplace of today’s graffiti, Philadelphia. This style features elongated vertical letters that seem to be stretched and if you’ve been to Phildelphia, you’ve most likely encountered it. It is extremely hard to read and has even been referred to as “Philadelphia’s encrypted language” by the art magazine Mass Appeal. Normally, the style is called “Philly style” or “Philly hand,” because it is very distinct.

Because graffiti is vandalism at its core, it quickly became popular with New York City’s gangs, and in turn became associated with crime, even though not all or even most graffiti writers in the mid 1970s were gang members.

As a result, the government was strongly urged by citizens to take a tougher stance on graffiti. The MTA, in turn, removed all of the subway cars that had been “bombed” and replaced them with brand new cars. By the 1980s, the government made a number of efforts to both prevent graffiti by increasing surveillance and security measures, such as barbed wire and fences. More severe penalties for those who were caught writing also were instituted.

Many graffiti artists chose not to quit writing, but instead to confront the challenge by finding newer, more impressive spots on the streets. The political atmosphere caused the stakes to rise for painters in New York City, and as a result, good spots to paint became increasingly valuable. Competition for them was fierce.

Consequently, one had to travel in a group in order to avoid any run-ins with gangs, so the laws that sought to diminish the gangs actually strengthened their hold on the graffiti world and probably infused graffiti with the hip-hop world for good.

Before the movement toward harsher penalties, the streets of New York were largely untouched by graffiti artists. When the MTA began increasing security measures for the new cars that they brought in, this was no longer the case. Walls downtown were quickly covered with characters (both written and illustrated), and rooftops became a graffiti artist’s very own billboard in the 1980s.

At this juncture, writers started to get increasingly innovative in their efforts both to stand out and “get up,” citywide and nationwide. To do this they would do pieces on freight trains or even vans and buses left unattended. Anything was fair game and could become a canvas if a writer had enough audacity to risk getting caught.

Because New York City officials were keen on preventing and removing graffiti at this time, most of the pieces were short-lived. Most graffiti writers had to paint often in order to get noticed. It can be said that these added challenges only inspired writers to find more unique, hard-to-reach spots that wouldn’t be covered so quickly.

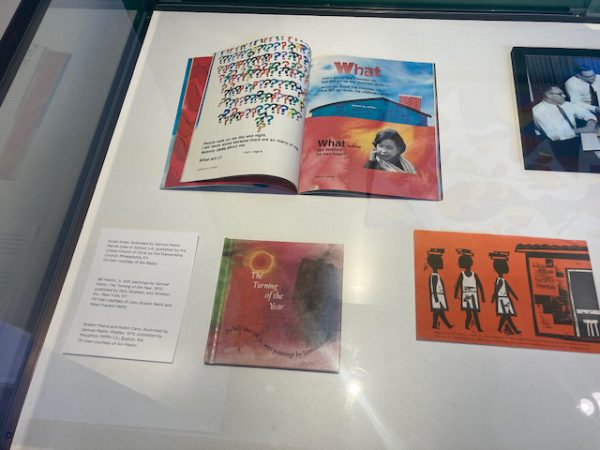

It was in the early 1980s when the art world largely began to recognize and accept graffiti as a form of art. Many writers started to open galleries and display their works more in formal settings. Artists like Fab 5 Freddy and Jean-Michel Basquiat opened the mainstream world’s eyes to both the growing world of graffiti as well as its association with hip-hop culture.

Graffiti became the subject of popular films and hip-hop songs as well, so it can be said that it had largely reached the mainstream by this time. From there, it proliferated even more nationally and globally.

Graffiti has always been a form of self-expression and therefore art, despite its tendency to deface public spaces. Some would argue that these works of art adorn public spaces while others might say it makes spaces more decrepit looking and contributes to a feeling of danger.

The argument continues today as writers continue to “get up” and “bomb” as often as they can in order to gain notoriety. Writers face many challenges, as laws have become harsher and competition fiercer, but those who are dedicated to their art still survive today.