We need to talk: the problem that is America’s Gun Culture

October 20, 2015

The dialogue about guns in this country must continue, because one of their current roles in our society—to create chaos and devastation—is unacceptable. The conversation cannot be stirred by too-frequent mass shootings and then fade to the backs of our minds as time passes the way it always seems to. The aim of the debate on how to curb gun violence should not be to attack the views of either political party. Instead, it should be a concerted effort to address this public health crisis in the United States.

People on both ends of the political spectrum should not become defensive when their positions are challenged. What is at stake in making progress is far more important than the interests of Republicans who want to keep their guns and limit government and Democrats who want to shame those on the right for their views.

In highly publicized massacres, as well as in less media-appealing homicides and suicides, people with guns decimate others and themselves. We can not, as a nation, drag our feet on this issue while innocent lives continue to be lost and others walk in fear. We must continue to push for steps in the right direction—whatever those may be—because our government’s current strategy of changing nothing and hoping for the best is failing and insulting the intelligence, and humanity, of Americans.

Listing the sites of the multitude of mass shootings in the recent past is not necessary because they are known all too well. There must come a time, and there is no reason that that time should not be today, when the majority of America realizes that our gun culture cannot continue this way.

In the aftermath of the Oregon shooting just a few weeks ago, Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush had an interesting take on how America should respond to the latest massacre. Bush was not sold on taking impulsive action by passing legislation to try to rectify the gun violence problem in this country. However, instead of doing so in an eloquent, reasonable fashion, he resorted to using the phrase, “stuff happens” during his muddled reasoning.

Imagine being a member of one of the families who had a son or daughter or brother or sister gunned down in the massacre at Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Ore., and then hearing a man aspiring to be this nation’s leader essentially remark, “Oh well, there’s not much we can do.” Clearly the solution to smoothing our future with guns is remarkably complex, but we must act on the belief that a safer nation is achievable and within our power to create.

If Bush had been speaking about an earthquake or a tornado—sure, stuff does happen. We certainly are not going to pass extreme weather control laws. However, his words, which he later stuck by, were insulting and ignorant. Bush’s comments do not reflect the views of the entire pro-gun community, yet they do echo a common sentiment—that gun violence is an inevitable reality.

According to the Center for Disease Control, in 2013, 33,636 people lost their lives in gun-related incidents. Considering that number should alert every American that this country suffers from a gun problem. Gun deaths only slightly trailed motor vehicle accidents as one of the leading causes of death in America.

Car deaths might be likened to gun deaths, because, like guns, cars are controlled by people and are clearly dangerous. In a recent article addressing gun violence, Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times described a reply he received to one of his tweets—a man sarcastically suggested that if Kristof believes in banning guns, then he must believe in banning cars as well.

“Actually, cars exemplify the public health approach we need to apply to guns,” Kristof wrote. “We don’t ban cars, but we do require driver’s licenses, seatbelts, airbags, padded dashboards, safety glass and collapsible steering columns. And we’ve reduced the auto fatality rate by 95 percent.”

The logic here makes sense. The vast majority of Americans do not believe in simply banning guns in the same way that nobody would try to ban cars. However, we can take measures to make them safer without infringing the rights of law-abiding gun owners.

There is a notion that those who commit violent crimes—particularly the mass, public murders that have become so routine in the United States—are going to obtain guns no matter what. Many believe that these people are crazy and hell-bent on committing violent crimes, so gun control measures won’t stop them, it will just stop regular people from being able to protect themselves.

This might not be so true. In UC Berkeley Professor Franklin E. Zimring’s work on decreased crime levels throughout the latter part of the twentieth century in New York City, he found that it was not increased arrests or shifting demographics that caused the drastic drop in crime rates. Instead, it was simple attempts to prevent crime in the first place that caused the decline. The NYPD began putting police officers in places where crime tended to happen frequently, thus slowing the rate of crime. The NYPD also enacted a controversial “stop-and-frisk” policy, which involved officers attempting to prevent crimes by checking on people they deemed suspicious. While this led to racial profiling issues of its own, it also led to a serious drop in crime. The crime that would normally take place in the places where police began stationing themselves did not then move somewhere else. It just didn’t happen. As a result, crime in New York City dropped 80 percent from 1990 to 2010.

The central argument of Zimring’s findings on this work is that crime, at its core, is an opportunistic exercise. Many crimes occur not because of an inherent desire to carry out such an act, but because of the ease and opportunity that is allowed to commit them. “Fundamentally, the New York story tells us that major assumptions that we’ve been making, not just in the United States but all over the western world, are wrong,” Zimring explained in a 2011 podcast with Scientific American. “And that the decisions to commit crimes are much more—if I can use a couple of buzzwords—situational and contingent than I thought.

“What that means is that if you can reduce the robbery rate on Tuesday, you’ve probably reduced the robbery rate this year. And if you can make a robbery that was going to happen on 125th street, not happen there, it probably won’t happen.”

This same thinking should apply to gun violence. Violence in New York decreased for one reason—the New York Police Department decided to put forth effort to deter would-be criminals. Impediments were put in place to prevent crime, and crime slowed down. If similar deterrents were put in place to prevent gun violence, it’s reasonable to think that the results would be similar. As Zimring put it, committing crimes is often not the result of a deep-seated desire for bad behavior, but rather, a situational and contingent response to the positions criminals find themselves in. Simply put, more bad things happen when there are more opportunities for crimes to take place.

In the United States, countless opportunities exist for bad things to happen with guns. In fact, this is true more so than anywhere else in the developed world. In 2007, the Small Arms Survey, a widely sourced center for studies on small arms and armed violence around the world, reported that civilians in the United States owned about 270 million guns. That comes out to 88.8 guns per 100 people. The country with the next highest number of guns per 100 people is Yemen, with 55. Yemen is followed by Switzerland with 46, Finland with 45 and Cyprus with 36. Among so-called “superpowers,” Germany is next with 30 guns per 100 people.

There is a similar disparity in gun violence around the world. According to the Human Development Index, in 2012, the United States had 29.7 homicides by firearm per one million people, which led all advanced countries. Switzerland had the second-most, with 7.7 homicides by firearms per one million people.

The Tewksbury Lab, a website committed to applying science to the larger world that is run by a University of Washington professor, found in 2012 that there is a correlation in developed countries between gun ownership and gun violence. Unsurprisingly, the United States is again at the top of the list, with not just more homicides, but more deaths in general caused by firearms than in any other country.

Even within the United States, states that have stricter gun control laws have fewer gun-related deaths according to economist, professor and journalist Richard Florida of The Atlantic and New York University. The evidence is present that the unique culture of guns in the United States leads to a unique culture of violence.

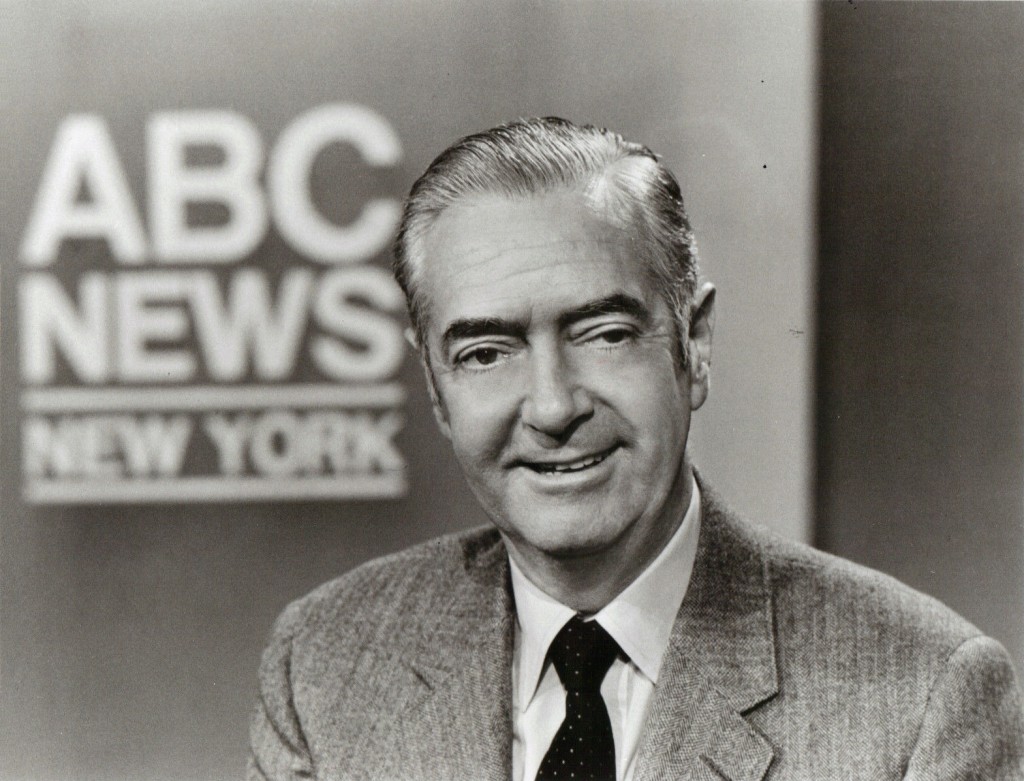

On June 5, 1968, in the immediate aftermath of Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, ABC News anchors Howard K. Smith and Frank Reynolds addressed the nation to console viewers and shed light on the tragedy that had just occurred.

“We had a disaster about five years ago, November the 22nd, 1963,” Smith said. “The president [John F. Kennedy] was assassinated by a mail order weapon, and since then the president—the present president—and some of the members of Congress have been trying to pass a law to make it harder for mad men to get their hands on weapons. In this country it is easier than in any country in the world for everybody to get a weapon.”

Does that sound familiar? That was in 1968, 47 years ago. Today’s outrage and rhetoric regarding guns is not new. And the gun control bill Smith referred to was “practically emasculated” in Congress, as Reynolds would go on to say. Fifty years later, and we’re still running in circles, ten steps behind solving this problem.

Let’s fast-forward to 2015 when President Obama strolled to the podium in the White House briefing room to address the nation regarding the individuals gunned down in Oregon. “There has been another mass shooting in America,” Obama began. He sounded dejected, but not because he was apathetic. The anger, even before it bubbled to the surface, was evident in his voice and in his physiognomy.

“It cannot be this easy for somebody who wants to inflict harm on other people to get his or her hands on a gun,” he continued. Forty-seven years later and news anchors and elected officials alike must say, regretfully after a tragedy, that we need to enact change, and yet they remain powerless. A divided Congress and a divided nation block progress.

After Smith’s remarks, Reynolds continued to harp—with tear-filled eyes—on the absurdity that we continue to allow these heinous events to take place without taking serious action. He recalled President Lyndon B. Johnson speaking on gun control, wondering, “how much more anguish must America endure from the sale of mail order rifles?”

Back then, in 1968, the nation was not recovering from the events in Aurora, Colo., Newtown, Conn., and Lafayette, La. Instead, America was in shock from “the murder of President Kennedy… the murder of Martin Luther King… [and] the attempt to murder Senator Kennedy,” Smith said. He was incredulous that Congress still could not pass a law designed to prevent such horrors. And to this day, nothing has changed.

The continuation of the gun conversation is key, but the cycle of routine outrage and inaction must end. Many people who want to protect their guns, as well as elected officials and candidates hoping to win or keep office avoid the real conversation. Republican presidential candidates like Mike Huckabee, Donald Trump and Ben Carson predictably shifted the spotlight after Oregon onto the admittedly real mental health issue that exists in this country.

Mental health is undeniably important, and the large majority of Americans agree that our system for dealing with its patients can be vastly improved. Absolving guns as part of the problem is naïve, though. “How can you, with a straight face, make the argument that more guns will make us safer?” Obama asked, exasperated.

The reality of mental health disorders in the United States does not mean that guns should not also be addressed. It is far easier for mentally ill people to act on violent intentions and leave devastation in their wake with firearms in their possession.

Students at the University were confronted with the issue of guns during midterms, perhaps more directly than many had been before. After a pointed threat surfaced against an “unspecified university near Philadelphia,” our safety came into question. Of course, law enforcement was present in conjunction with Public Safety, but students had to seriously think about the gun culture in the United States and how it should be dealt with.

It is time that the country as a whole does the same thing—thinks about whether guns being an integral part of society should be a hallmark of a nation we want to live in. Trying to reform gun legislation in the United States is not meant to be an infringement on liberties or attempts to “take your guns.” It is an attempt to make our country safer, in any way we can.