An honest review of studying abroad

February 28, 2017

If you ask someone who has studied abroad about their experience, chances are they’ll respond with some laudatory phrases. “It was amazing!” “It was fantastic!” “It was the best experience of my life!”

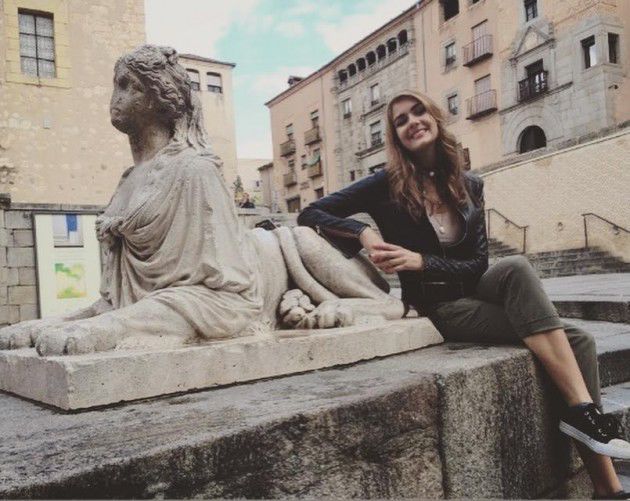

I’m not claiming that these descriptions are false. I definitely had the most incredible experience in Madrid, where I spent the Fall 2017 semester.

But as a student preparing to go abroad, these phrases were of little use to me, and the effect they had on my subconscious actually proved deleterious once I made it to Spain. Because I’d been so conditioned to expect rainbows and butterflies, any time I was less than ecstatic overseas, I felt that something was wrong with me. Furthermore, those quaint charts provided by preparatory services depicting the “rollercoaster” of culture shock and adjustment aren’t as helpful as one would hope. I want to clarify that these generalizations only tell, in my opinion, half the story.

To all soon-to-be-abroad students: I want to share with you my experience in the hopes that you can get something out of it that you might not have gleaned from five-minute conversations between recently returned acquaintances.

First of all, it was a long time before I processed what was happening to me. Actually, I don’t think I fully processed the scope of my experience until I got back. I’ll get hit with the realization, sometimes, staring at pictures of myself outside thousand-year-old buildings thinking “Wait, I was there.”

Even while abroad, I fully recognized my lack of absorption. I remember walking through a forest garden outside the Nymphenburg palace in Munich and telling myself to be present, be present. Unfortunately, living in the present is one of the most difficult tasks for human beings—try meditating, if you haven’t already, and you’ll understand. Focusing on your attempt will undermine the entire project. So once your feet hit the ground in your country of choice, try not to succumb to anxiety about living each moment to its fullest extent. That lack of realization is part of the moment itself.

That being said, I benefited a lot from not having my phone. I have been guilty of painful dependence on my phone since at least the 10th grade. I’m sure we can all relate to that uneasy feeling that accompanies a broken phone and how we can never fully enjoy ourselves while our device is out of commission. Yet, as essential as cell phones feel, they’ve only been around in this capacity for ten years or so. Decades of students living abroad before the invention of the smart phone have somehow enjoyed themselves! Of course it’s nice having GoogleMaps to guide you around foreign cities (Tip: download the offline version so you don’t need data), but realize that you don’t need it. Every time my phone would die, or I’d run out of Internet, I’d tell my friends we were “going 80s.” I pictured myself wandering around Prague with a printed-out map and pocket translator like my aunt did 30 years ago. She survived. It’s doable!

Because of this, I saw so much more. My first weekend in Spain, we took a trip to Valencia. Our city hostel was a 30 minute bus ride from the beach. As we drove down the street, I had my nose plastered to the glass, in awe of the architecture and the weird signage and the funny transactions I watched go by. I’m not kidding when I tell you that I actually witnessed a distraught middle school boy trying to win back his girlfriend—she was not having it.

I also significantly added to my experience simply through making the effort to get out. The first few weeks were difficult, in terms of figuring out where to go or what to do or with whom to do it, particularly because I chose a non-Villanova program. I had class 10 am—2 pm, and after that, everyone in my school returned home to their host families for dinner and stayed there. Being a little too restless to sit in my basement bedroom for more than the time it took to siesta, I chose to explore, albeit alone. I did many things alone in the beginning, and at times felt very alienated. But some of my soon-to-be friends were just as lonely alone in their rooms watching Netflix, and by the end of the trip weren’t half as familiar with our town as I had become. I’m a runner, so I ran. But I walked, too, in the evenings before dinner. I would wander in and out and around every single street and alley in my town. I fell in love with Alcalá in a unique way because of the effort I put into my relationship with the city. As a side benefit, I stayed pretty fit, which is dope.

I also went to every extracurricular opportunity provided by my university. The second week in Spain, my school posted about a round table pre-election bilingual debate at a sister university in Madrid. Even though at first I had intended only to listen, within 10 minutes I was unable to resist participating with the group. People switched between Spanish and English, I learned a ton about current politics in Spain and I left with new contacts in my phone.

From that moment on, whenever lying in bed appealed to me more than whatever potential event I had planned for a given day, I would simply force myself to follow through with plans. Doing things—anything—made the days go by faster.

And here was the real catch about which no one had told me: when you’re abroad, contrary to popular belief, not every day flies by. I arrived in Spain unprepared-for that. Sometimes, the days crawl.

I learned to cope by devising a sort of list of semi-productive pasttimes. I had my sketchbook, and would draw in the square. I bought a novel in Spanish at the local bookstore. I worked on scholarship essays and internship opportunities for next semester. I planned international vacations in minute detail. I joined a gym, which I could not recommend enough. It’s a great place to make friends and I burned so much time (and calories) there. I researched bars, museums, parks and monuments that I wanted to see in Madrid, and planned a mini-excursion almost once a week. I journaled.

I came to understand that my experience was just that—my experience. Whatever it was—cultural or fun-filled or introspective—it was the only one I would ever have. And realizing that was liberating.

Now, I can tell you with clarity what I took away from studying abroad. I became enormously self-sufficient. I learned to appreciate so many things—the closeness of my family, the modern middle-class conveniences, speaking English—that I’d formerly taken for granted. I gained exposure to the lifestyles of friends from Oklahoma, Arizona, Wisconsin and Missouri. I became fluent in another language. I laughed in another language. And the fun stuff: I tried hundreds of new foods, saw works of art and fantastic buildings I’d only ever read about, visited places that were absolutely surreal, danced in nightclubs until 7 in the morning, scream-sang drinking songs in Irish bars, stumbled upon a Sunday morning street market in Sevilla and ate pancakes in an airport at 4 am. I went to a daytime EDM concert in an art studio built from a converted monastery, swam in the Mediterranean sea, discussed philosophy on a pier in Galway, went to a Real Madrid game, made friends with a squad of British guys who danced on tables with me at Oktoberfest, attended an 8-hour Spanish barbeque and, as cliché as it sounds, lived to the fullest. For every sad or lonely moment there was one of absolute rapture. For every moment I longed to come home there was one where I wanted to stay in Spain forever. And that, I think, is why people who’ve studied abroad respond the way they do.

That is why, when you ask me about Spain, I’ll tell you it was amazing, fantastic, the best experience of my entire life.