The Villanovan Book Buzz: Toni Morrison’s “A Mercy”

November 3, 2021

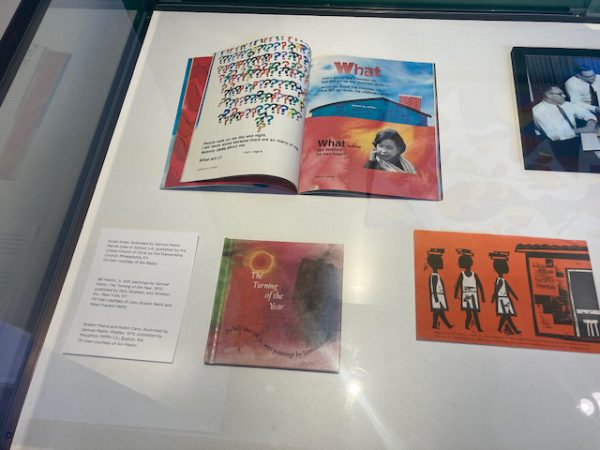

Toni Morrison’s best-known works include the “Bluest Eye,” “Beloved,” “Sula” and “Song of Solomon.” First published in 2008, “A Mercy” was added to the celebrated author’s collection of novels.

To fully grasp the significance of Toni Morrison’s “A Mercy,” it is necessary to understand that though America is a nation that relied on brutal enslavement for its founding political and economic liberty, American history is established on the exclusion of Black culture. In a novel that is difficult to read yet impossible to put down, Morrison shows us that in the early days of Colonial America, a new land prospered while its Black men and women faced violent, psychological trauma.

In the first pages, readers are presented with confessions and reassurances from an unnamed voice that says, “Don’t be afraid” while Morrison constructs a scene of blood and darkness. This unnamed voice talks of nights, of dreams and of Minha mãe. She tells of the moment her mother gives her up to a white man out of preference for her brother. Morrison plunges into a narrative before the reader has any idea what is going on, but she seamlessly presents the beginning ideas of a girl’s sexuality and promiscuity, of maternity sought from a foreign mother and of the hypocrisy of white man’s religion.

In the subsequent pages, readers come to understand that it is 1690 in Virginia. This mysterious, unnamed narrator is Florens, a 16-year-old Black girl. Florens is given to Jacob Vaark, a white businessman and property owner whom she calls “Sir,” in settlement of the debt owed to him by the Portuguese slave owner she calls “Senhor.” Jacob, a man who claims to morally object slavery and who is insistent on accumulating his own wealth, forms a makeshift family of himself and four women – one white, one mixed race, one Black and one Native American. In addition to Florens, there is Jacob’s wife Rebekka, an immigrant from London whom the servants call Mistress. Lina is a Native American woman sold to Jacob by the church who rescued her from the disease that plagued her tribe. Lastly there is Sorrow, a mixed-race outcast who survived a shipwreck before she was taken into the care of Sir and Mistress.

The women are all orphans on the homestead of a land Morrison presents as wild, scrappy and untamed. Lina, a nurturing and motherly character, acts as both Mistress’ right-hand woman and Florens’ protector. All the while, Sorrow remains alone in the illusion of the company of a companion she calls Twin. Rebekka must cope with the death of her four children, and with the eventual death of her husband, she is driven to the point of despair. In her illness and mental absence, the homestead crashes. The loose chains of sisterhood, motherhood and friendship fade away as the women retreat to isolation. Rebekka orders young Florens to find the Blacksmith who may cure her, a free Black man who once worked with Jacob.

There is much to be said of Florens’ eventual love and desire for the blacksmith. Morrison depicts Florens’ mad infatuation as a hunger, a desperate yearning for bodily connection. But in a hurricane of events, her passion is deemed only wild and childish, and her love is dismissed. “You are nothing but wilderness. No constraint. No mind.”

On the last pages of the book, the voice of Florens’ mother mysteriously returns. She recounts her horrific journey through the Middle Passage, saying, “I welcomed the circling sharks, but they avoided me as if knowing I preferred their teeth to the chains around my neck, my waist, my ankles.” She recalls a white man raping her, as well as his apology and consolatory gift of an orange. She recounts the moment in which Vaark offers a “mercy” to her desperate plea. It is in this casual act by Vaark that the meaning of Morrison’s title comes to full fruition. For Morrison, there are no miracles from God, only casual, careless mercies offered by white males.

Morrison creates pervasive themes of motherhood and reproduction throughout, but it does not come with ease or beauty. From sex and birth comes sexual violence and death, and from motherhood comes loss, pain and malevolence. For Sorrow, a confusing, uncertain and potentially unreliable character, motherhood seems to be one of her only human skills. After losing her first child, she finds wholeness in motherhood at the cost of a likely violent and loveless consummation.

“A Mercy” begins where it ends. Embedded in the truth of her mother’s sacrifice is the knowledge that Florens’ owner is dead, and that the young girl will never receive her mother’s message. Left an untamed orphan by the white man who has mercy on her, she is to be rejected by a man who could never truly love her. Morrison taps into the experience of Black women during this time and of the danger, trauma and violence that perpetuates the Black condition at the expense of white advancement.

Through her varied, vivid and beautiful language, Morrison depicts the Black experience in a beautiful new world rooted in poisoned soil.