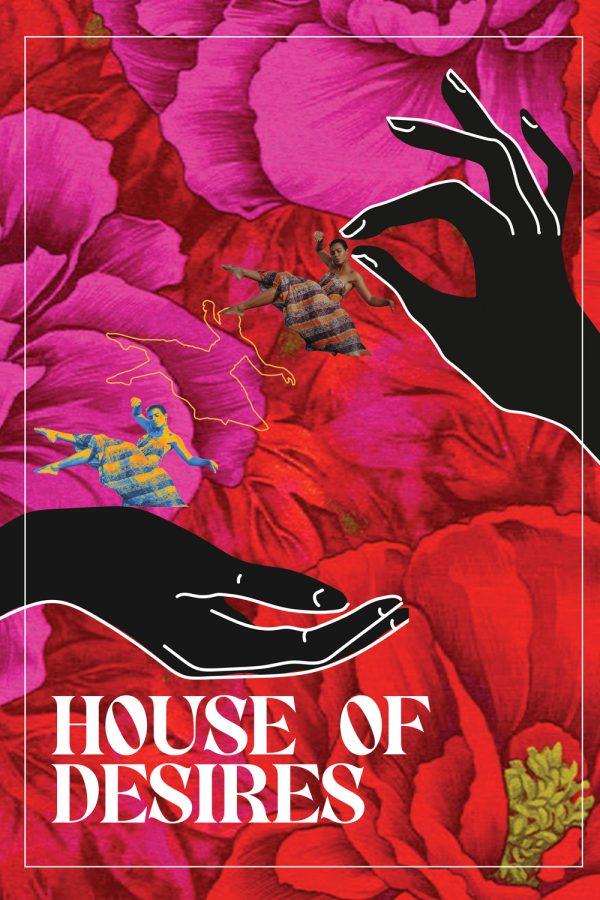

The Love Shack: “House of Desires” Reviewed

November 15, 2022

The Villanova Theatre presents “House of Desires,” a romantic farce written by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a 17th-century Mexican dramatist, philosopher, poet and Hieronymite nun. “House of Desires” opened at the Mullen Center on Nov. 10 and will run through Nov. 20. All shows are at 8 p.m. except for on Sundays when showtime is at 2 p.m. “House of Desires” is reminiscent of Shakespeare, as characters grapple with unrequited and forbidden love that leads to mistaken identities and an acute incident of transvestism. There is a vast web of characters all heavily integrated into each other’s lives.

The play begins with Doña Ana (Teya Juarez), who is pursuing Don Carlos (Joshua Peters), angrily lamenting Don Juan’s (Tomas Alfonso Torres) perusal of her. Meanwhile, Doña Leonor (Emma Drennen) has come to reside in the home of Doña Ana and her brother, Don Pedro (Sheldon Shaw), after being stripped away from her lover, Don Carlos, whom her mother, Doña Rodrigo, does not approve of due to his low socioeconomic standing. The various assistants, Celia (Taylor Molt), Castaño (Paul Goraczko) and Hernando (Brandon Hunter) are responsible for both serving their respective masters and orchestrating the grand deception.

Director James Ijames puts a modern spin on a seemingly archaic piece of late-Baroque Spanish-American literature. “House of Desires” becomes—what the youth of America know and love—the next “Love Island” or “Too Hot to Handle.” Before the play starts, the theater is awash with a modern flair: Whitney Houston’s “I’m Your Baby Tonight” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” play as the audience looks upon a pink-lit stage with large, sparkling cacti and funky-colored furniture waiting for the fun to begin.

As the actors take to the stage, the formalities of the 17th-century slip away. Each character becomes a reality TV or telenovela stereotype: Don Juan, the ukulele-playing Rico Suave, Don Pedro, the Tibetan singing bowl-obsessed pretty boy and Don Carlos, the smooth-talking ladies’ choice. The women, too: Doña Rodriga, the overprotective, overbearing helicopter parent, Doña Leonor, the golden-haired Helen of Troy and Doña Ana, the spoiled hopeless romantic.

All of the actors were geniuses of physical comedy, utilizing the little space and minimal props to their advantage. Torres especially brought smiles to the many faces out in the audience with his attempts to serenade Juarez with his ukulele and loud, flourishing stomps and overdramatic smolders.

The assistants who, to their masters, hold small, meaningless roles in their lives, in reality are responsible for the great deception that plagues all. The three of them—Goraczko, especially—were hilarious.

The role of Castaño was beloved by all: his grand scene in Act II involving that acute incident of transvestism elicited laughs and hoots of excitement from the audience. Goraczko was not afraid to directly interact with the audience, using them to only improve his own performance. It made the material much more relatable and the plot easier to understand. Goraczko was beckoning the audience to engage and to put themselves in the shoes of each of the characters. For that, amongst many other reasons, “House of Desires” was a hit.