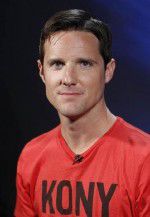

In conversation with Kony

March 21, 2012

In the six years of Invisible Children’s existence and the three years of the University’s chapter of Invisible Children, nothing has ever gone as viral as the Kony 2012 video put up on March 7. The 30-minute Youtube video has had over 83 million views, and the number keeps rising.

The video summarizes the conflict in Uganda surrounding the violence of the Lord’s Resistance Army led by Joseph Kony. It encourages people to take action in making Kony famous to eventually assure his arrest through urgently seeking out influential and powerful change-makers. The video is played out through the eyes and experiences of Jason Russell, the film’s creator, and is given the insight of a child with some commentary from his son Gavin. Some critics say Russell became a “bridge” character for people to help relate to an issue more than 8,000 miles away, while others claim it’s an over-simplification of an extremely complex issue.

The University’s reactions to the viral video have been similar to the reactions worldwide. There is now a wide awareness of who Kony is, but there is also a good amount of criticism and backlash about the movement.

On Monday, March 19, Timothy Horner of the peace and justice department gave a talk during a Catholic social teaching and human rights program at the University. After studying genocide for years, as well as having a keen interest in the continent of Africa, Horner has established his position as somewhat critical of the Kony 2012 movement. During his talk, he measured the good, but mostly the danger, of Kony 2012.

“There are unintentional consequences we don’t know about to the international community and to Americans,” Horner said.

He discussed his criticism on Russell and the Kony 2012 movement, but not the Invisible Children organization. Bringing up the issue of colonialism, he described how this movement could be seen as “neo-neocolonialism.” He said it’s a problem of not listening to the voice of the other, but rather focusing on what one person thinks is right for the people he is speaking for. He showed a reaction of northern Ugandans seeing the video for the first time and how their confusion soon turned to anger. They voiced their discomfort with others making money on their misfortune, and they were generally confused about the message in its entirety.

“It’s not that the video is a representation of Uganda, but they’re a part of it,” Horner said. “That voice of what Ugandans think was never factored into the video.”

The same day as Horner’s presentation, the Invisible Children chapter of the University held a screening of Kony 2012 along with a brief talk by a few of the national organization’s roadies and a Ugandan representative, Sharon Proscovia.

Proscovia put to rout some disbelief about Ugandans’ support of the Kony 2012 movement.

“I know one thing-no one can challenge my testimony,” Proscovia said. I lived it. It compelled me to come and share my story and inspire people to help stop this war.”

When asked about whether or not her family and friends in Uganda supported the movement, Proscovia enthusiastically replied how happy and proud everyone she knew was of her and the movement.

The executive board of the University’s Invisible Children collectively agreed the criticism allowed for more extensive dialogue about the issues of violence in Uganda, the mission of Invisible Children and the identity of Kony.

Junior Andrea Zinn, president of the University’s Invisible Children organization, appreciates the new light shining on the problems in Uganda.

“The most important thing Invisible Children does is accomplish the mission of people hearing about this war,” Zinn said. “No one had heard about it for 20 years at that point [of Invisible Children’s start] and now, 26 years later, people are finally taking an interest in it.”

Simplifying the complex issue, though, has been a serious criticism of Kony 2012. Chris Horne, senior vice president of Invisible Children stressed the importance of putting the video into the context of other Invisible Children work.

“If you situate it in terms of the broader mission and not just a one-time deal, then you’ll see it’s the pinnacle of what they’ve been aspiring toward for almost a decade,” Horne said. “It’s more thought out and planned than a lot of people perceive it to be.”

Social media has been a driving force in the Kony 2012 movement. Critics have coined the term

“There is a simple media structure for a complex world,” Horner said. “They polarize the world in lieu of the truth. This video implies that awareness is a solution in itself and that’s too simple of a solution to a complex world.”

The number of views on the Kony 2012 YouTube video, however, is one testament to the number of people social media can affect.

“It’s one style that has flaws, but the flaws aside still get you directed toward a bigger goal,” Horne said. “No, it’s not perfect, and yes, it’s right to question the complexity of it, but there’s a greater good. There’s evidence in that by the amount of support and funding going to the programs on the ground.”

Invisible Children on the University’s campus has significantly raised its fundraising numbers by over $6000 this year from last year. Invisible Children is firstly an advocacy and awareness program. The University group feels this will eventually diminish the problems of violence and children armies and see it as an effective long-term solution.

The group is currently working on the logistics for the University’s involvement in “Cover the Night,” the event taking place on April 20 as advertised by the Kony 2012 video. It encourages people inspired by the issue to post signs of Kony in hopes to make him even more famous, causing him to be a better known threat and an important person to arrest.

Whether people are opposed to the Kony 2012 movement or in support of it, both sides agree it offers a chance for constructive dialogue and deeper learning about issues in Uganda and about Kony.

“We’re really excited about all the attention that Invisible Children has finally gotten,” Zinn said. “And we hope people choose to educate themselves on the issue we’re been confident in and remain confident in.”