Legislators replacing ObamaCare, looking ahead to new plan

February 1, 2017

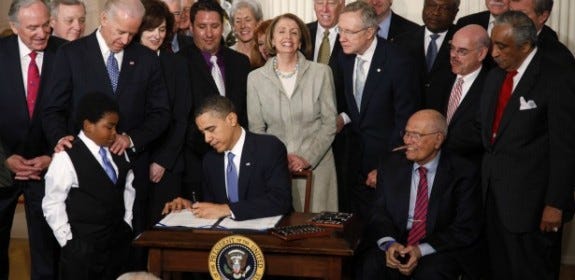

Since gaining control of both Congress and the White House, Republicans now can set the public policy agenda. Republicans can enact into law what they campaigned on, but among their most pressing and politically difficult campaign promises is repealing and replacing Former President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Even before the law’s implementation though, ACA inspired criticism, but the pre-ACA status quo was even less popular. Patients with preexisting conditions may have previously been denied health insurance. The ACA fixed that problem by banning insurer discrimination based on preexisting conditions. Pre-ACA left many people uninsured, so many Democrats are eager to keep the law intact.

Yet despite the ACA’s benefits, the ACA has serious problems. The folks with preexisting conditions are undoubtedly better off than they were in the pre-ACA, but at a cost to the young and healthy. Since it doesn’t let insurers hike premiums or deny coverage for people with preexisting conditions, they hike prices on healthier clients to cover for losses they incur. Some insurers have left the federal government-run healthcare exchanges altogether. ACA’s individual mandate was meant to stop the bleeding by keeping insurers from incurring losses by making everyone buy insurance, but it failed because younger, healthier patients decided that they could forgo expensive insurance until they got sick and pay the mandate’s fines.

This is an ironic position for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: It protects some patients while rendering insurance uneconomical for others. Nevertheless, if the healthcare market fails due to Republicans’ dearth of a replacement plan, the public will blame them. Frankly, since President Donald Trump lacks an eye for detail, replacing ACA could be just that much more difficult. But sometimes what’s difficult is also what’s necessary.

The current administration has some options for how they can operate—but within serious constraints. Republicans plan on using a budget resolution process called “reconciliation” to repeal and replace the law. Reconciliation requires a majority in the House and a simple majority in the Senate to pass (51 votes). Additionally, reconciliation can be used once a year and affects only taxation and entitlement spending provisions. Since Congress didn’t produce a budget last year, however, reconciliation can be used twice this year. So the Republican plan right now is to partially repeal ACA in one reconciliation bill and replace it in another.

That sounds fine until you consider the flaws with the Republicans’ plan. The problem is that the reconciliation bills would probably only directly affect ACA’s taxation and spending provisions—meaning they can’t directly touch its regulations. But the regulations are decimating the healthcare exchanges. The exchanges could sustain further damage if the Administration immediately repeals the individual mandate since insurers would lose more money. Moreover, there isn’t even a consensus about what a replacement of ACA should look like, with a minority of them questioning whether there should even be a replacement at all. So at the moment, Republicans are considering a partial repeal through reconciliation that won’t go in effect until 2019, giving them time to hash out their replacement plan differences. But “repeal and delay,” as the strategy is called, has numerous political and economic risks according to healthcare experts.

These aren’t small problems, especially given that they only have 52 seats in the Senate. If Republicans simply repeal ACA but can’t consolidate around a replacement plan, then according to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections, tens of millions of people could lose health insurance and Republicans would be the ones to blame. For this reason, Trump recently tweeted that Republicans should be careful in replacing ACA. He’s right.

The situation sounds bleak, but there’s hope. According to Yuval Levin, a healthcare policy expert at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, Republicans could use the two reconciliation bills to bypass ACA’s regulations by creating a new stream of funding for healthcare provision. In doing this, ACA’s regulations—which are attached to the law’s spending provisions in some key respects—would become irrelevant because Republicans would be at liberty to attach new rules to the new funding. This new funding could utilize tax credits and permit states to regulate healthcare markets with certain caveats attached.

For instance, instead of implementing an unconditional protection for people with preexisting conditions, legislators could stipulate that customers would be protected only if they maintained continuous coverage. This way, even healthy patients would have an incentive to buy insurance plans. The tax credits would allow people to buy insurance in the individual market. Other than those stipulations—that a plan is approved by a state government and consumers maintain constant coverage—consumers can purchase whatever plans they want and be protected if they have preexisting conditions.

Some legislators won’t like such a plan (or for that matter, any other replacement plan). Replacement plans with similar regulations have already been introduced in Congress, but many Republicans haven’t backed them. For this reason, some have expressed skepticism about repealing ACA until a replacement has been formulated. However, once they realize the gravity of the current political situation, replacement-skeptical Republicans would have more than enough reason to get in line with Republican replacement plans.

Levin also says that there’s no guarantee that Republicans can pass two reconciliation bills this year. If that happens, legislators might have to scrap the reconciliation idea and compromise with moderates to reform ACA. This could mean loosening ACA’s preexisting conditions protection while temporarily keeping ACA’s subsidies and individual mandate in place.

Whatever they do, the current administration needs a carefully crafted consensus plan. Otherwise, their leftwing critics might be proven right.