Professor and team digitize emancipation ads

April 25, 2017

On Jan. 1 1863, amidst the third year of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln passed the Emancipation Proclamation legally ending slavery. The first reaction of many newly freed slaves was to search for family members who had been sold or run away.

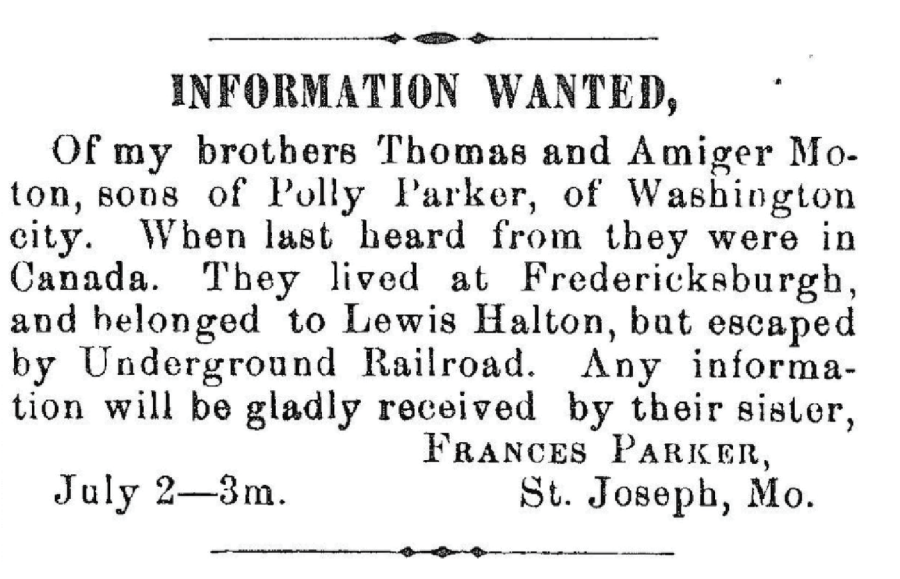

Judith Giesberg Ph.D., history professor and director of the Graduate Program in History, is attempting to piece together the answers of African-American genealogical history post-emancipation through her online database, “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery.” Giesberg, with her team– Margaret Strolle, James Christopher Byrd, Karyna Hlyvynska, Bonnie Loden, Daniel Runyon and Falvey Library reference librarian, Jesse Flavin–have digitized about 1000 “Information Wanted” advertisements placed in African American newspapers by former slaves searching for lost family members. The goal of the project is to assist researchers, historians, and genealogists piece together the fragmented history of African-Americans post-emancipation.

Giesberg began her project in Philadelphia after seeking out Margaret Jerrido, archivist at Bethel AME Church. Jerrido stumbled upon boxes of such advertisements preserved on microfilm in the church. As partners in the project, Giesberg and Jerrido began digitizing the advertisements from the Christian Recorder, the oldest African-American published newspaper in the nation. Giesberg and Jerrido have since transcribed advertisements from five other African American newspapers from the time, discovering advertisements from 1863 to 1902.

“Family is an essential part of the human experience, yet enslaved people were routinely denied family in the U.S. They formed family bonds, anyway, and even when separated by sale, they held on to memories of their loved ones,” Giesberg said. “Each Information Wanted ad tells a story that an enslaved mother, child, husband remembered about their loved ones, even after years of separation.”

One ad from 1886 placed in the Christian Reader of Philadelphia reads: “Information wanted of my son Allen Jones. He left me before the war, in Mississippi. He wrote me . . . that he was sold to the highest bidder, a gentlemen in Charleston, S.C. Nancy Jones, his mother, would like to know the whereabouts of the above named person.” A majority of the advertisements are placed by mothers looking for children, siblings for siblings and children for parents. Other ads are of fathers looking for children and spouses in seach of each other. Christian Recorder ads were often placed by clients’ pastors, who paid one dollar and fifty cents for a onetime ad, four dollars for one that would run entire year in biweekly publications. Giesberg and Jerrido have also stumbled upon ads sharing good news that families have been reunited.

Giesberg and Jerrido’s project has received much media attention, including a segment on CBS Evening News and an interview on NPR.

“History is stacked against enslaved people, because their literacy was carefully outlawed and their access to information restricted by slaveowners,” Giesberg said. “The Information Wanted Advertisements represent the moment in which that tide turned—emancipation. The first thing freed people did was seize what had been denied them: information about family members. These ads open an important window into the transition from slavery to freedom.”