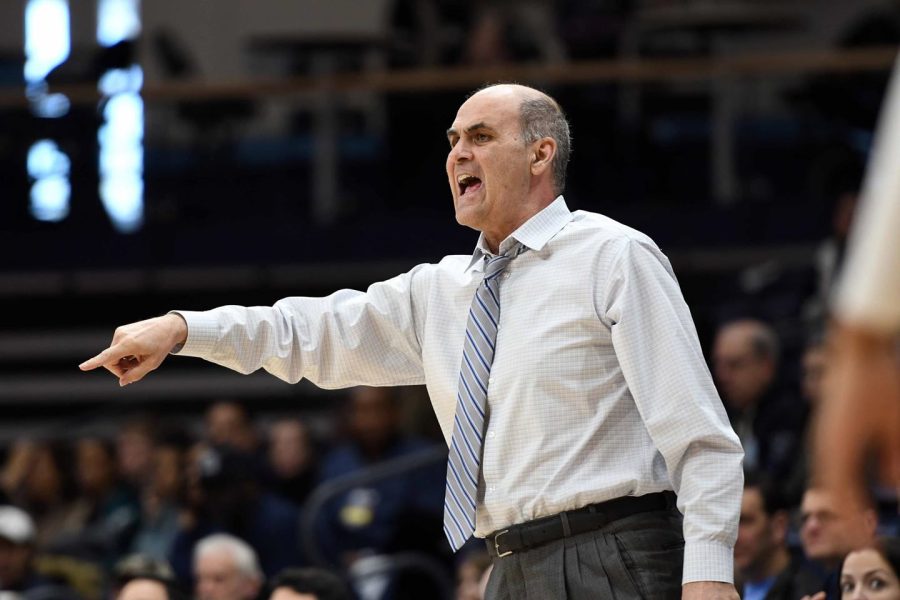

Soap Operas, Ponies and Winning Basketball: A Final Farewell to Coach Harry Perretta

Courtesy of Villanova Athletics

Soap Operas, Ponies and Winning Basketball: A Final Farewell to Coach Harry Perretta

May 1, 2020

It’s early on a Sunday morning in February, and Harry Perretta is uneasy. Some game day jitters are not unusual for the 64-year-old, who, on his own accord, will admit to having nervous tendencies. Yet, on this day, the nerves are more intense. One can hardly blame Perretta for the extra anxiety he is experiencing. After all, the magnitude of today’s contest surpasses that of almost any other during his 42 years as the head coach of Villanova women’s basketball. Today, for the final time, Perretta will traverse the sidelines in front of the Wildcat faithful.

Tip-off is set for 1 p.m. The clock reads nine at present, meaning most coaches would be with their team by now, participating in the pregame meal and overseeing shootaround. Perretta has a different routine, however. It started when Joe Mullaney became an assistant back in 1996. After coming into the program, Mullaney quickly noticed that Perretta’s uneasiness before games was rubbing off on the team. He suggested to the head coach that he turn his pregame duties over, a proposal which Perretta was quick to adapt. The pair stuck with it for the next 24 years.

“The only two times he came to a shoot around,” Mullaney recalls, “we lost by 40”.

So Perretta is on his own on this unseasonably warm morning, and he needs something to ease his growing apprehension. A walk seems like an appropriate remedy, but it would be nice to have a friend join him. The coach has plenty of possible companions to choose from, yet, given the moment, there is one that serves best, his neighbor Mary Ann Shields.

Shields and Perretta have known each other for 15 years. She is one of the limited number of people that Perretta is close with outside the world of basketball, and her outsider’s ear is just what Perretta needs to get his mind off things. The two walk for about a half hour through their Drexel Hill, Pa. neighborhood. The houses are familiar to Perretta, who has lived at his current home for the last 20 years along with his wife, Helen, and their two sons, Stephen and Michael. Helen played for her husband during the late 80s and the two were married in 1996. Stephen and Michael, true to their lineage, are both students at Villanova currently. As Perretta had hoped, the conversation with Shields is soothing, and by the time he returns back to his house for a quick shower, he is beginning to feel a bit better.

After the shower, it’s off to campus. On most days, Perretta would swing by Wawa now – a maneuver right in line with a man who has lived in Delaware County since he started high school. A breakfast of oatmeal is customary, but on game days this stop is bypassed, for it’s simply impossible to take in food on such a queasy stomach.

It’s a 20-minute journey from driveway to Villanova for Perretta. The short drive is nothing compared to some of the much longer trips Perretta has taken during his career. Life on the road is an inescapable part of coaching – yet it’s an aspect of the job which Perretta would be happy to do without. Flying is particularly repulsive, a sickening endeavor only to be taken on out of complete necessity. Buses are better, yet still problematic in stop-and-go traffic.

Yes, if there was a way to reach his destination using his own car, Perretta would find it. He took road trips to Chicago, Tennessee, Florida – all while driving alone. He would leave a day or two in front of his team and find somewhere logical to stop along the way, sometimes to see some old friends, other times to recruit a high school player. The countless hours at the wheel were passed with audiobooks from Cracker Barrel – a little known secret which Perretta lets me in on.

“I don’t think people know this,” Perretta says, his voice revealing the pride he holds in this peculiar piece of knowledge. “You can go to a Cracker Barrel in Pennsylvania, and you can rent a book on tape and drive to say, Florida, and you can return the book to a Cracker Barrel [there].”

Perretta parks and exits his Ford Flex, setting foot on grounds that are both exceedingly familiar yet starkly different from the school where he commenced his work more than four decades ago.

“When I got here, no West Campus, no Connolly Center, no nursing school, no Davis Center, no Commons, no South Campus,” he remembers.

The year is 1978, and Perretta has just graduated from Lycoming College, a small liberal arts school in Williamsport, Pa. Like many recent college graduates, Perretta is in need of a job. He wants to coach, that’s what he had been doing for the last three years at Lycoming after an ankle injury put an end to his own playing career. When Perretta was a sophomore, Dutch Burch, the program’s head coach at the time, offered him a position as an assistant for the JV team. Eventually, when the JV coach left the following year, Perretta was handed the reins to the junior varsity squad while also assisting Burch with the varsity. It was an experience Perretta excelled at, and one that now, as a 22-year old, has him scouring for any opening in the field.

He tosses in an application to be the women’s basketball coach at Villanova. The program is just nine years into its existence, and the position is listed as part-time. Perretta is one of 65 applicants for the role and, given his youth, is initially eliminated from consideration. His luck quickly turns, however, when he discovers a chance connection – the position’s hiring manager, Mary Anne Dowling, is married to one of Burch’s former players at Lycoming. This linkage, along with a strong letter of recommendation from Burch, is all that’s required for Dowling to give Perretta his chance. Suddenly, just a month after his college graduation, Perretta finds himself the head coach of Villanova women’s basketball team.

It’s 11 a.m. and game time is rapidly approaching. The Davis Center is where Perretta heads now. The building houses facilities and office space for both the men’s and women’s basketball programs at Villanova. On the first floor, at the end of a long hallway, lined with pictures and trophies from the program’s past, sits Perretta’s office. It’s an expansive room, much larger than the cramped setup of the old Jake Nevin Fieldhouse where the program was based until 2007.

During an average week, you might find Perretta sitting behind his desk, recounting some of his many stories with a couple of players who stopped by. There might be old basketball friends there too. Many of them like to come to practice to catch up with the coach, as do his former players, who often bring their families and children along with them.

There are likely more team members down the hall, doing school work in the conference room. Perretta will stop by and check on them. While it may be the biggest cliché in college athletics, academics really have always been the priority in Perretta’s program, with 99% of his athletes who stayed for four years receiving their degree. Almost everyone stays too. Up until last spring, not a single women’s basketball player had transferred out of the program for 20 years, a remarkable feat, especially in a sport which maintains one of the highest transfer rates nationally. Yes, for Perretta, the Davis Center is as much a place for basketball operations as it is for community.

“His relationship with the players is beyond the four years that we’ve all played for him,” Laura Kurz, a student-athlete from 2006-09 and Perretta’s assistant coach for the last five years, says. “Any time we need help or advice or we’re trying to change careers, [for] a lot of people, Harry’s that first call.”

There is no questioning Perretta’s willingness to help. Just ask the man he gave $21 to stay at a YMCA, only to, after going back to check on him, see him climbing into a brand new car. Or ask the blind couple for whom Perretta stopped his run to help cross the street before proceeding to lead them straight into a wall. It’s this generous spirit which, although sometimes not rewarded in the outside world, endears him to all who play for him.

“Forget basketball,” redshirt freshman Maddy Siegrist says. “You can put down a basketball and never play again, and he’d still care about you.”

The decision had been made over the summer, but was not announced publicly until just before the start of the 2019-20 season. Perretta’s final year has been one of celebration, a chance for the man who has given so much to receive a little in return. He’s picked up some notable presents – a piece of the original Palestra floor from Penn, his favorite chicken wings from Drexel, a subscription to the Daily Racing Form along with $300 cash for the racetrack from DePaul. Somehow, this hodgepodge of gifts seems to fit Perretta flawlessly. He’s particularly fond of horse racing and has been since high school when his friend’s parents introduced him to the sport. Perretta subscribes to TVG, a television network dedicated to showing races from across the globe, and he enjoys placing bets recreationally – though never beyond the budget he allots himself in advance. The coach also appreciates television. He was an avid viewer of “All My Children,” a soap opera which ended in 2011, ironically, after 42 seasons on air – the same number of seasons Perretta has coached the Wildcats. Now, he relies on “Law and Order” and the History Channel to get his fill.

On a Tuesday morning, I am seated in a folding chair inside the sacred Davis Center walls along the sideline of the team’s practice court. I’ve come to see what Perretta says he will miss the most upon his retirement. Despite his competitive success – 783 total wins, twenty, 20-win seasons, 11 NCAA Tournament births, 11 WNIT appearances, five Big East championships and 18 Philadelphia Big 5 titles – practice always provided Perretta the most fulfillment, allowing him to teach and interact more with his players. Once this season, he even suited up for a practice himself, determined to show his team he still had it.

“It wasn’t pretty, I’m not going to lie to you,” senior Mary Gedaka laughs. “I mean he worked hard, don’t get me wrong, but he was a little slow-stepped.”

Stretching and warmups are first. After 15 minutes or so, the coach enters. He is wearing a white Villanova women’s basketball t-shirt with baggy navy blue basketball shorts extending below his knee – the kind first popularized by Michigan men’s basketball’s “Fab Five” back in the 90s, but which have seemingly been out of style for the past ten years. His hair, plentiful during his early coaching years, now appears in gray, wispy strands and covers only the sides and back of his head.

I’ve heard stories of the old Perretta practices. The ones brimming with intensity, the ones filled with screaming demands, the ones where, by the session’s conclusion, the coach felt as if he had “actually ran up and down for two hours.” This, however, was not the aura of the practice I watched that morning. It hadn’t been for the last five years or so, Mullaney tells me. Perretta mostly observes, allowing his assistants to dictate the various drills. His left leg drags as he paces the court’s perimeter, perhaps a result of yesterday’s outdoor run. (Perretta never goes a day without 50 minutes of exercise. He used to run outside more often, but as he’s aged, his routine has shifted to ellipticals and bikes). A basketball is pressed tightly against his hip in what is a perfect visual metaphor for the inseparable relationship he has with the sport. During a break in play, I hear him chatting with one of the team’s practice players about the Philadelphia Catholic League finals, a local high school championship played the night before. At one point he ventures to the far end of the gym, where sophomore Sam Carangi is rehabbing an injury. The two talk for a few minutes before Perretta continues his roam. He interjects periodically to critique a player’s defensive stance or to stress that they take an open shot, but mostly he just watches. Eventually he takes a chair and seats himself beneath one of the baskets. Recently, Perretta often is unable to stand for the entirety of the two hour practices; his energy and strength simply aren’t what they used to be. It may not be the fiery and frenetic practices of the past, but it is clear I am still observing a special scene, one with a man still very much in love with basketball and with his program.

The Blue Demons enter the contest ranked 12th in the nation with a record of 25-3, including a 15-1 mark in the Big East. The ‘Cats, meanwhile, sit at 15-11 overall and 9-6 in conference play. Luckily for Villanova, Perretta has pulled off some upsets in his day. When you coach for 42 years, you’re going to have some pretty big wins and for Perretta, perhaps none was larger than the 2003 Big East Tournament Championship. There, his team put an end to UConn’s 70 game winning streak – the longest ever in Division I women’s basketball at the time – with an earth-shattering, 52-48, victory. That same team would go on to reach the Elite Eight of the NCAA Tournament, Perretta’s deepest run ever in the event.

It was following this performance on the national stage that Power Five schools began to express interest in hiring Perretta. It wasn’t a decision he took lightly; after all, he had the opportunity to more than triple his salary. He opted to consult Father Dobbin, Villanova’s President at the time and a man Perretta considered a close friend.

“I told him the offer, and I said what do you think?” Perretta recounts. “He said, ‘Har, I think you should get up, go back to your office and get back to work. You’re not going anywhere.’ I got up and I said, Father, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

So Perretta came back that next day, and he is still coming back now, nearly 20 years later. This year’s ‘Cats may not have the same talent as that historic 2003 squad, yet, after losing four of their top five scorers from a year ago, the team’s winning record is an accomplishment in itself. Today, it is looking for a signature win to boost its rank in the crowded Big East standings.

More than 2000 fans bustle in anticipation as the teams take the floor. Play begins, and Cameron Onken, one of three Wildcats celebrating senior day this afternoon, opens the scoring with a triple. It’s an open look and a good sign for Perretta’s offense, which has never been shy when it comes to pulling the trigger from deep.

Many in the basketball circle know Perretta for his famous, “five-out” offense – a motion scheme centered around the idea of having all five players on the floor outside of the three-point line. The reality, however, is that Perretta has had a number of innovative offensive styles over the course of his career. He started with the “spread,” the strategy which he first made up in college at Lycoming. It generated good spacing, but a coach must always adapt to his players, so when the three-pointer began to become a bigger part of the game, and more sharp-shooters started coming into the program, Perretta made the switch to the “five-out” to help facilitate more looks from beyond the arc. The concept was utilized for years, and to great success, but Perretta was always one to make adjustments, even if it meant committing one of coaching’s cardinal sins – revealing his hand.

“I would pick other coaches’ brains,” he explained. “I would show them what we’re doing and then I would ask [the other coaches] if they had anything they thought I should add or subtract.”

For the final three to four years of his career, Perretta settled on an “option” offense – an approach where one side of the floor was overloaded in order to make it difficult for defenses to bring weak side help on drives to the basket. An “X and O” coach who has dedicated his entire life to the game of basketball, Perretta says he got the idea from the unbalanced line in football.

Whatever the offensive game plan happened to be, it certainly would not lack sophistication. The complexity of the offensive system is part of the reason it became a pattern in the program for freshmen to redshirt their first season on campus. A year of learning was often beneficial before players were thrown into game action, where they would be subjected to one of Perretta’s trademarked sideline tirades should they make a mistake on the floor.

Sparked by Onken’s opening triple, the ‘Cats would go on to hit three of their four attempts for deep in the first quarter. After the opening 10 minutes, Villanova holds a 20-19 lead, an advantage which it would expand to 33-30 by halftime. Belief is building. This is the game the team had thought about all year, the fairytale send-off. It is the type of game that’s played at the end of a Hollywood sports film, and the Wildcats had 20 minutes to ensure the script proceeded as they desired.

If anyone thought the first half was the best basketball Villanova had played all season, their opinion would quickly be swayed after watching the next two quarters. Perretta’s option offense continued to flow, with the Wildcats connecting on 17 of their 32 second half shots. Perhaps most impressive, however, was the invigorated defense on display. The ‘Cats were simply unwilling to give up an easy shot, resulting in a lowly 27.8% field goal percentage for the Blue Demons over the final 20 minutes of play. A 10-point lead after three quarters looked promising, and when the margin was stretched to 17 halfway through the final frame, the celebration began to diffuse throughout the arena. The public address announcer told the crowd that Onken had just recorded a triple-double, only the second ever in the program’s history. In the end it was Siegrist leading the way for the ‘Cats with 29 points, breaking the freshman season scoring record in the process.

When the final horn sounds, the team engulfs their coach in a circle of chaos by the bench. The celebration soon moves to center court, where Perretta and his team gather with the more than 50 former players who have decided to attend the festivities. The activity is so hectic, Perretta will end up watching a recording several days later to better digest the occasion. Gedaka is joined on the court by her mother, Lisa Angelotti, who was named the 1986-87 Big East Player of the Year while playing for the Wildcats. The pair are one of three mother-daughter combinations to be coached by Perretta. Sure, the age range of those on the court is wide, but as Perretta’s assistant of 21 years Shanette Lee says, “Everybody that’s come through this program has been instilled the same values. We can come back and interact with each other so freely.”

This freedom of interaction is clearly on display as multiple generations join together to honor one man’s legacy. As a video tribute plays on the scoreboard, the group unites with the crowd in a chant that consists of just one word but somehow says so much more.

“Harry! Harry! Harry!”