Climate Change, Refugees, and Migration: A Summary of Lepage Webinar

Brian Luppy/ Villanovan Photography

A panelist speaks at the Lepage Center’s recent event.

March 29, 2023

The Albert Lepage Center for History and the Public Interest at Villanova is holding a six-part series on investigating climate change from a historical perspective. With a new monthly panel, each webinar has aimed to examine the overarching issue of climate change through different perspectives, ranging from climate justice activism to its impact on global security. The fifth of this series took place on March 20th, where a panel of three leading experts discussed the rapidly growing repercussions of climate change on refugees and migration.

Dr. Maria Christina Garcia, Howard A. Newman Professor of American Studies at Cornell University, began the panel by expressing misconceptions about being a refugee.

“[When we think of refugees,] we rarely think of those displaced by environmental disasters,” Garcia said.

Her research curate’s conversation around this issue in hopes of climate migrants being wholly included in political discussions on refugee acts.

In addition, Garcia spoke about Temporary Protected Services (TPS) and its impact on displaced persons due to climate migration domestically. Moreover, while TPS can be an effective tool in the United States, the accessibility of it is limited to those already inside the states, with no aid to anyone hoping to flee countries with uninhabitable conditions brought on by the changing climate.

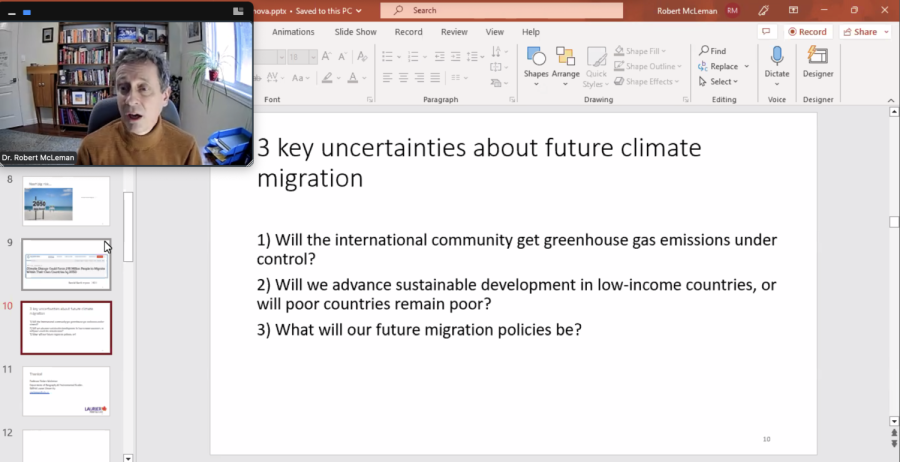

The next panelist, Dr. Robert McLeMan, professor of Geography and Environmental Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, spoke about the growing climate pressures that will affect the world. He mentioned a study completed by the World Bank in 2021, which predicted that the strenuous increase of climate change could “…force 216 million people to migrate within [their] own countries by 2050.” There lie extensive risks in all parts of the world, with differing natural disasters exacerbated by climate change, including extreme storms, floods, droughts, and rising sea levels.

“[I urge companies and communities to] work quickly and reduce greenhouse gas emissions… [so that we may] limit much of the displacement that would otherwise occur,” McLeMan said.

Amali Tower, Founder and Executive Director of the NGO Climate Refugees, spoke of this issue from a practitioner’s point of view.

“[The most pressing barrier to aiding climate migrants stems from] problematic cherry picking of who deserves international protection,” Tower said.

She boldly stated that migration had become the most significant impact of climate change, disproportionately affecting those in vulnerable countries where it is increasingly burdensome to unpack this slow onset impact.

The driver of Tower’s conversation was the political issue created by climate migration. That is, the fact that countries have deemed border security a more pivotal issue than human security. The lack of an enforceable policy framework has shown that wealthier countries that drive up pollution spend more on border security than climate adaptation funding. Marginalized groups only become more vulnerable and susceptible to the effects of climate change when the government does not provide a suitable means for changing the mobility path.

Dr. Lynne Hartnett, Department of History Chair and Associate Professor of History at Villanova University, moderated this panel. She commented on how climate consequences’ current disproportionate and unfair effect on less-developed countries will eventually spread.

“These conversations are important because if the trends we are seeing now continue, everyone will be affected by the consequences of climate change and the temporary or permanent relocation that will result,” Hartnett said.

Climate change has become a sizable driver of migration and displacement. Its significance should not be ignored. This is why the world cannot turn a blind eye to those affected by climate displacement, as devastating environmental disasters and their consequences will not be contained much longer.

“I think when we fail to look at an issue in historical context, we fail to understand it fully… [It] allows policymakers to see what lessons can be learned from the past to make informed decisions about humanitarian, immigration and environmental policies,” Hartnett said when asked how the historical outlook on climate change can affect conversation in the modern age.

Indeed, the historical context has a growing impact on current events, and to create the most effective course of action, these two ideas must be viewed alongside one another.

The final installment of this series, “The Effects of Climate Change on Cities,” takes place on Wednesday, April 12th, from 6:00 to 7:15 p.m. via Zoom.