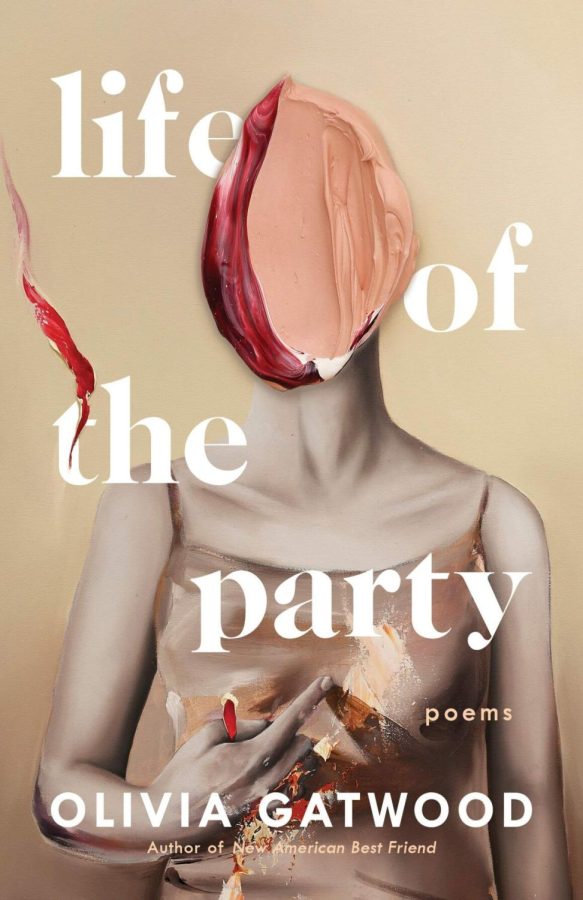

Book Review: Life of the Party by Olivia Gatwood

This week’s Book of the Week.

September 8, 2021

*Disclaimer: The following piece discusses a book that mentions murder, sexual assault, and rape.*

Poetry is often disregarded as an outdated form of writing exclusively for the pleasure of those who wear billowing and for torture in English classes. However, Olivia Gatwood’s book, “Life of the Party,”is one of many examples of the ever-evolving and heart-wrenchingly relatable nature of poetry.

Gatwood is a 29-year-old poet originally from Albuquerque, New Mexico who studied fiction at Pratt Institute in New York, NY. She is known for her performance poetry, her writing workshops and, according to her website, her work as a “Title IX Compliant educator in sexual assault prevention and recovery.”

She has been an advocate from an early age. One of the most notable examples is an incident that happened during Gatwood’s high school years, when she was one of several women who worked at a local bakery to come forward to report the business to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for sexual harassment. The women received a settlement.

Gatwood is also one of two hosts on a podcast titled “Say More,”a show in which she and fellow poet Melissa Lozada-Oliva discuss everything from their relationships to pyramid schemes to the founding mothers of the abolitionist movement. While Gatwood’s work spans many mediums, her voice and opinions remain constant. She is self-assured, opinionated, brilliant and so deeply unlike the outdated schema many think of when poets come to mind.

Published in 2019, “Life of the Party”focuses on the concept of femininity and queerness being conveniently left out of stories matriculated by true crime media. While the definition of “true crime” is self-explanatory as real crimes that have happened, the cases most widely discussed are those that are unusual, horrific and absurd. Often, the crimes are not the ones that, while horrible, have become the norm, like women being followed multiple blocks on their way home or queer people disappearing and never being heard from again.

Gatwood focuses on the fetishization within the media of true crime — how white cisgender women and men are described as heroes, and their athletic and academic accolades are the reasons for any unlawful death deserving rage and grief. However, an overwhelming amount of crimes against people of color and the LGBTQ+ community are purposefully ignored, collecting dust in the corners of society’s minds. Black transgender women and sex workers face the most heinous of judgements, yet receive the least support in looking for them when they go missing, let alone seeking justice for their lives. Along those same lines, their assailants — usually white males — have their accolades and families propped up like shields around their names and reputations, defending themselves against the victims and their families as reasons for why they deserve the benefit of the doubt and the freedom to go on with their lives without consequences.

Gatwood studies her own conceptualization of the feminine identity and queerness through poetry about her own life — her friendships, her relationships, her childhood — in addition to the stories of violence against women as well as women who perpetuate violence, like Aileen Wuornos, a woman serial killer from the late 1980s.

The difference between Gatwood’s work and the work of traditional media produced within the genre of true crime is her determination to accomplish due diligence for the woefully ignored violence against people who know all too well that, as Gatwood puts it, “It is a privilege to have your body looked for.”

All of these experiences and ideas are bound together by both structured as well as free verse poetry, with lines such as, “i wanna be all the girls i’ve ever loved/mean girls, shy girls, loud girls, my girls/all of us angry on our porches” (Girl (After Ada Limón)), and, “Laughter is not about humor/it is about acknowledging a shared joy./Laughter is about bonding/Example: When I hear men laughing/I do not enter the room./I crawl home in the dark” (Mans/Laughter).

This combination makes this book a testament to both the blessings and curses of girlhood and the coming to terms with the experiences that carve out parts of who girls are and the content they have consumed that has profoundly shaped their perceptions of the world and the mirror.

These poems hold so much significance and weight in any reader’s heart, especially in the wake of the protests about the rape of a 17-year-old girl by a member of the Phi Gamma Delta (Fiji) fraternity at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln (UNL), in addition to the new rulings in Texas concerning the criminalizing of receiving, providing and aiding in the access of abortions. The criminalization of existing as a woman (and anyone else who does not identify as a cisgender white male person), is a subject hotly debated and not well protected. Violence against women, whether by a fraternity member or by the state, is not the protection of women like so many argue. It is the massacre of their safety, their health and their rights, which are concepts highly emphasized in all of Gatwood’s work, not just her writing.

It is no surprise that Gatwood has had many fraternity members walk out of her public readings of her work. But, it is also not surprising how many people feel heard and seen by her poetry. Her opinions and knowledge about exploring her own identity, her obsession with true crime and her expertise on growing up as a woman come together to create a one of a kind experience that haunts all her readers in a way which teenage girls are especially familiar with. Many teenage girls can find great comfort in knowing that they are not alone in this mess, not in the least.

While you wait for Gatwood’s forthcoming novel, “Whoever You Are, Honey,” enjoy the haunting lines of poems like “Mans/laughter,” “Ode To My Favorite Murder,” “Aileen Wuornos Takes A Lover Home” and “All Of The Missing Girls Are Hanging Out Without Us.”

Hold these words close, even long after you are “silent, and dead, and still the life of the party,” as Gatwood writes in her poem Girl (After Ada Limón).