Kavanaugh Hearing Highlights a Dark Part of College Life

Kavanaugh Hearing Highlights A Dark Part of College Life

October 2, 2018

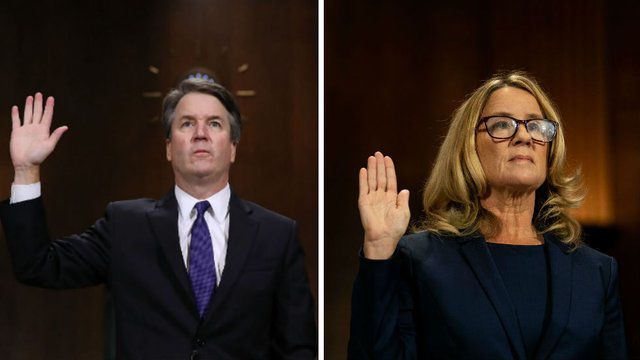

Brett Kavanaugh is 53 years old. He is a son, a husband, a father, and a Supreme Court nominee. He is also, quite possibly, a sexual harasser.

In the past two weeks, allegations of sexual misconduct have surfaced during Judge Kavanaugh’s nomination hearings that threaten to throw his confirmation off-course. Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, a professor at Palo Alto University in California, has accused her former high-school classmate of attempting to assault her at a party. Julie Swetnick, another classmate, submitted an affidavit stating that Kavanaugh had a history of date-rape drug use and gang-rape participation in the early 1980s. A fellow Yale alumnus named Deborah Ramirez chimed in that an unsolicited Kavanaugh exposed himself to her in 1983. Kavanaugh’s compatriots are quick to point out that all three allegations date back more than thirty years. Should a grown man really be judged by his poor teenaged decisions?

It’s a relevant question for Kavanaugh’s peer group, pondering the choices that they wish they could change, but I would argue that the matter holds the most relevance for the college students of today. If your worst decision now would impact the rest of your life, how would you act differently?

In 1983, Brett Kavanaugh stood in roughly the same position as most Villanovans: he was a smart young college student with a future that felt light years away and a party to go to that night. Like us, Kavanaugh had put in the hard work required to attend a prestigious university and eagerly seized an opportunity to take a break from his rigorous coursework and spend time with friends. He had been raised with the same Catholic moral values that guide our own community, and attributes much of his later success to these ideals. Yet, if Deborah Ramirez is to be believed, his actions at this party divorced sharply from any ideas of ethical conduct. The conditions that led to Kavanaugh’s indiscretion that night are the same conditions that foster absuive decisions on our own campus today.

First, the 18-year-old was no stranger to privilege. His own hard work can be attributed to his admittance at Yale, but there’s no denying the leg up afforded by eight years of private education followed by Jesuit boarding school. He had grown up in Bethesda, Maryland, an affluent suburb bordering Washington, D.C., and his parents were both in the legal profession. When it came time to pay for Yale, the Kavanaughs certainly had it easier than most. At private colleges like Villanova, whose steep tuitions increase exponentially from one year to another, you’re likely to find many students who can easily relate to the kind of upbringing Kavanaugh enjoyed. This is not to say that wealth or privilege are inherently villainous, but it underlines a significant point: young, impressionable Kavanaugh was not accustomed to hearing the word “no.” Further, there was no reason for him to believe his actions would have far-reaching consequences; if need be, he could call upon his influential parents and his impressive academic credentials to get his career off on the right foot. Money can’t buy everything, but it can buy the sort of future security that many on our own campus can anticipate, and the idea of amnesty later can make it much easier to reconcile immoral choices now.

Second, Kavanaugh surrounded himself with a peer group, and a culture, that corroborated the mistreatment of others. Later in his freshman year, he would pledge and join the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity. More recently, Yale’s chapter of this fraternity earned national notoriety (and a five-year campus ban) for chanting “No Means Yes, Yes Means A****” outside the women’s dorm; this same culture of misogyny was pervasive during Kavanaugh’s time, when pledges would customarily break into their female classmates’ rooms and steal underwear to display on campus as part of their “hazing” initiation. Although Kavanaugh was not yet a brother during the time of Ms. Ramirez’s alleged assault, it’s clear that he was already mingling with like-minded peers. Ramirez explained that Kavanaugh’s exposure was meant to be a “joke,” and young Brett had found the perfect audience to laugh along.

Phrased this way—a drunken mistake, a joke, a blight on one night but certainly not a lifetime—the actions of Brett Kavanaugh sound much less like those of a monster, and much more like another funny story from last Saturday night on campus. Only when it is carried through 30 years, heard in the voice of its victim, and amplified by the drama of a Senate hearing can we understand the accusation as the severe misdemeanor it really was. Regardless of any maturation Kavanaugh has done in the convening three decades, the allegations of his past victims have severely damaged his bid for the Supreme Court and utterly dissolved a lifelong belief in his security from professional consequence.

It is my opinion that we on the Villanova campus would be better dissolving this belief in ourselves before ever making our own large-scale mistakes. Ours is an opportunity that Brett Kavanaugh and many others would kill for: to live our young lives with care, beholden if not to our own honor than to our own self-interests. Let’s use it to support, and not harass, our classmates. Everybody knows that a joke isn’t funny when you have to explain it, particularly when this audience has a hand in deciding your future.