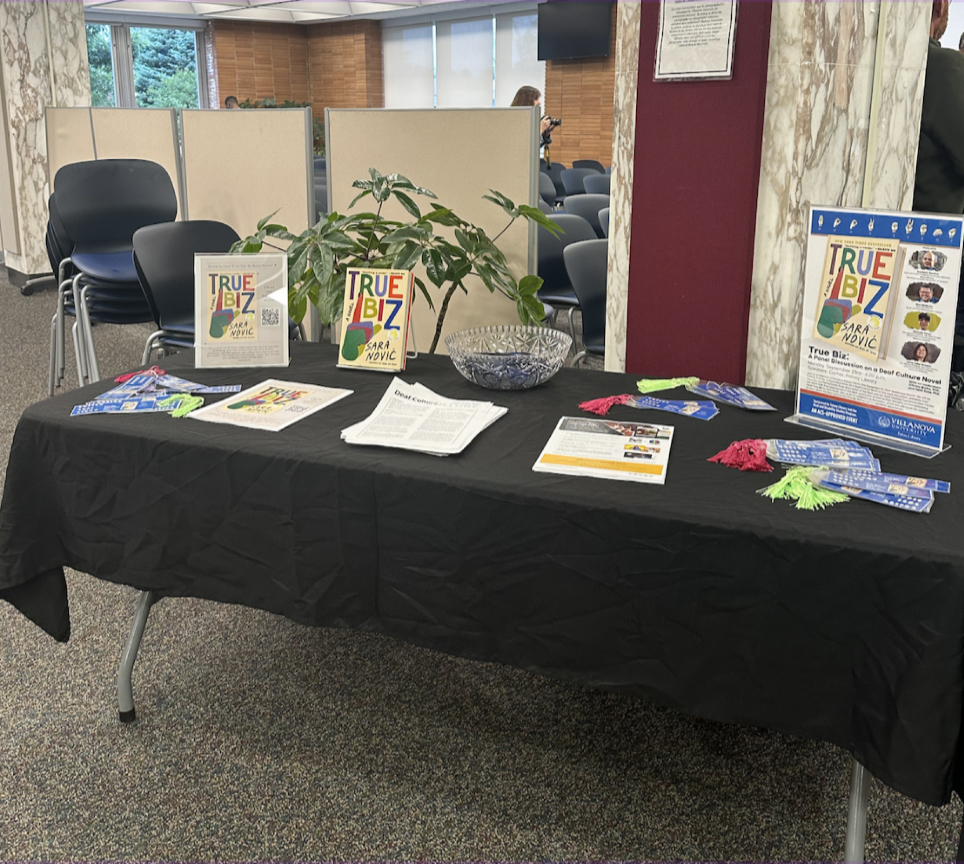

On Monday, Sept. 23, Falvey Library hosted an event on Deaf culture to celebrate September as Deaf Awareness Month.

The event, a panel discussion on Sara Nović’s bestselling Deaf culture novel, True Biz, took place in the Speaker’s Corner of Falvey Library. Panelists Michelle Foran, Neil McDevitt, Amy Vadakin and Dominic Gordine led the discussion. The event was co-moderated by Communications professor and ASL, or American Sign Language, Area Coordinator Dr. Heidi Rose and Special Education Professor and Disability & Deaf Studies Program Director Dr. Christa Bialka. There were three interpreters for the panelists and the audience.

Foran is an ASL Professor at Villanova University. McDevitt is the Executive Director of the Deaf-Hearing Communication Centre and the mayor of North Wales, Pennsylvania. He is the first Deaf person to be elected mayor of a municipality anywhere in the United States. Vadakin is an ASL Professor at Villanova. Gordine is a Board Member of the Pennsylvania State Association of the Deaf and an advocate for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community.

The panel covered panelists’ thoughts on the novel, their own experiences and educational journeys, their perspectives on cochlear implants and the role of advocacy in informing their identity as a Deaf person. Themes including language, community, identity, belonging and acceptance were explored throughout the event.

The panelists began with a discussion of True Biz. They described how their personal experiences resonated with those of the protagonist, Charlie. McDevitt explained how he too grew up as the only Deaf child in an ASL class and consequently felt like he was put on display as the “teacher’s pet.” This resulted in a feeling of isolation from his peers in his youth, even feeling embarrassed of his parents signing to him.

Vadakin similarly described her upbringing as the only Deaf person in her family, ultimately leading to a feeling she named “dinner table syndrome:” feeling alienated from conversations at the dinner table because of the difficulty of trying to read multiple lips at the same time, making it so she was unable to follow the conversation. Vadakin’s family did not know ASL, so the communication barrier was particularly prominent.

Gordine, on the other hand, had a much more positive childhood, as he attended a school for the Deaf, and his mother learned signed language. Everyone around Gordine signed, allowing him access to communication and peers like himself. While Gordine’s adolescence was different than the character Charlie’s, he described the profiting off of Deaf people described in the novel as anger-inducing and a “unifying experience among Deaf people.”

Unlike Gordine, Foran primarily connected with the novel’s author, Nović, as both Foran and Nović were born with the ability to hear before their hearing eventually declined into deafness later in life. Foran described how her family neither knew nor had a desire to learn ASL, but instead wanted her to get two cochlear implants, a point of contention in the Deaf community that was also discussed at length by the panelists.

A cochlear implant, or CI, is a device used for severe hearing loss that essentially replaces the function of the cochlea, a structure located in the inner ear, by electrically stimulating auditory nerve fibers. It allows an individual to learn the sounds of speech and, potentially, be bilingual in sign and speech. However, despite these benefits, cochlear implants are largely regarded as challenging and even problematic, particularly for children prior to the age of two, as parents have to decide whether their child should undergo this invasive and permanent surgical procedure. Moreover, some parents may not want their child to get a cochlear implant, particularly if the parents are also Deaf or have a connection with the Deaf community, which has its own language and culture.

McDevitt explained how he recently considered getting a cochlear implant because the effectiveness of his hearing aid was dwindling. However, there is a “critical time window” for this procedure, he signed, as at his age of 51 his brain is no longer malleable. Children, on the other hand, have a greater advantage to seize the opportunity of this technology. This is because language outcomes are much better when one receives a cochlear implant early in life due to the greater amount of time exposed to sound and language.

McDevitt compared the cochlear implant to LASIK eye surgery to illustrate that, unlike the common perception, cochlear implants are not a cure for deafness. While LASIK can give an individual perfect vision, cochlear implants can only give a person approximately 20 to 30% more hearing, rather than perfect hearing. In the past, cochlear implants were marketed as something they were not, signed McDevitt, but they are attempting to be more holistic in their approach.

The coordinators then invited panelists to further share their own experiences being Deaf and how this played a role in their educational journeys.

Vadakin described how she went to a school for the Deaf and had access to Deaf teachers, peers, sign language and culture. She characterized this a “wonderful experience” for which she is thankful.

Likewise, McDevitt initially attended a school for the Deaf but left for a mainstream public high school because he wanted to be with his neighborhood friends. However, he was the only Deaf person at this school, and consequently lacked models of ASL from the Deaf community. McDevitt ended up attending Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., the world’s only bilingual university for the Deaf, which he described as a “life-changing” experience.

Gordine attended the Pennsylvania School of the Deaf until his sophomore year of high school, when he transferred to Model Secondary School for the Deaf, located on the Gallaudet campus, for his final two years. Here, Gordine too was exposed to Deaf leaders, peers and countless opportunities.

Foran’s experience was unlike those of the other panelists. She attended a public high school, where she struggled to learn spoken English and read. She received her first hearing aid at the age of 27. At the age of 40, she became ill and was hospitalized for two weeks, during which time she became completely Deaf. Foran was ultimately able to overcome this as she learned ASL and was exposed to Deaf culture, making friends and finding a new family in the Deaf community.

The panel concluded with a discussion of the role of advocacy in each of the panelists’ identities as Deaf individuals, as well as what they want people to know about the Deaf community and how they can support those who are Deaf.

In his youth and adolescence, Gordine’s identity was centered around the fact that he was Deaf. He later realized he did not know his identity and has since expanded his identity to include being a person of color, too. Gordine aims to represent and advocate for Deaf people of color, as well as hearing parents because many are unsure of how best to support their child.

For Foran, advocacy is being there for someone late in Deafness like herself. She felt that she was “not Deaf enough” and aims to support those with similar experiences.

McDevitt emphasized that those involved in business and law have the best opportunity to become advocates. People should look at their workplace’s policies and ask difficult questions, ensuring that Deaf individuals are not being discriminated against. McDevitt also brought awareness to the need for interpreters, which are mainly white and female.

Students should continue to learn about the Deaf community and its culture, and advocate for those a part of it. This can be as simple as speaking up against discrimination or learning basic ASL, or as far-reaching as studying to become an interpreter. Whether one is Deaf, hearing or somewhere in between, it is essential that Villanovans welcome and embrace Deaf culture on campus.

This event was sponsored by Falvey Library and the Deaf and Disability Studies Program. Falvey Library plans to hold more panel discussions and events throughout the semester.