Cultural Studies Program Hosts Former Black Panthers

Courtesy of David Fenton/Getty Images

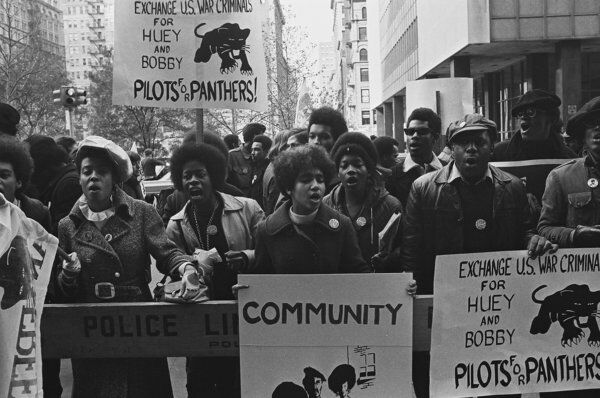

Women played an important role in the Black Panther Party.

April 21, 2021

On Tuesday, April 13, the University’s Cultural Studies Program sponsored a panel discussion with former Black Panther Party (BPP) members and other Black activists. Panelists Diane Fujino, Matef Harmachis, Dequi Kioni-Sadiki and Hank Jones spoke about their book, “Black Power Afterlives: The Enduring Significance of the Black Panther Party,” which is available to order through Haymarket Books. The book serves as a helpful timeline of the Black Power movement, from the founding of the Black Panther Party until present-day.

Jones, a former member of the BPP, explained how the brutal murder of Emmett Till in 1955 propelled him into action. He joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee before joining the BPP at age 27. While most men joined at age 17 to 23, Jones was already married with three kids when he became a member. He was drawn to the Party because it “went from theory to practice.” Jones criticized the way in which the media’s attention to the Party only focused on the fact that it was an armed group. He stressed how Party members had to defend themselves because no one else was going to. He explained that in the mid-1960s, African-Americans were “marginalized, disregarded and unserved.”

While never a member of the BPP herself, Kioni-Sadiki seeks to educate people on the legacy that the Party has left. The BPP created more than 60 survival programs, including free breakfast for children in school and free healthcare clinics. She said that many social programs Americans have today were first created by the Party and that no one had heard of sickle cell anemia until research by the Panthers. The movement also paved the way for lead testing.

Multiple panel members made sure to point out the important role that women played within the BPP.

“The role of women in the Black Panther Party is downplayed,” Jones said. “They were the backbone of the party.”

Acknowledging that men are usually the face of the Party, Jones went on to say that “we [the men] were too busy dodging bullets and on the run and locked up. The women kept the party functioning”.

Kioni-Sadiki noted how words like ‘radical’ and ‘extremist’ distort the reality of freedom fighting.

“We’re taught there’s something wrong with being radical,” she said. “But you can call me radical anytime you want. ‘Radical’ means getting to the root of the problem.”

Her husband and former Panther, Sekou Odinga, served 33 years as a political prisoner. While she celebrated his release in 2014, many former Panthers are still in or have died in prison. Harmachis noted how Chip Fitzgerald died after 51 years in prison.

In 1969, J. Edgar Hoover, the former director of the FBI, deemed the BPP as the largest internal threat to the country. Multiple panel members remarked how, once Hoover made this public statement, the Panthers had targets on their backs.

“We were much more than just an armed group,” Jones said. “We were a reaction to police violence.”

Jones spoke of how integral the Party was to the safety of the Black community in these cities. In addition to the various survival programs created by the Party, they would also protect the elderly people in their communities by escorting them to run errands.

Jones reminded audience members that there is still work to be done in the United States for African Americans to truly feel safe. Jones and Sadiki-Kioni brought up the worrying rise of fascism in the country, which can be explained by the “systems being threatened”–the systems in question being the countless American institutions that perpetuate systemic racism. He closed the discussion by saying, “This is not a free country. Not even close.”

To learn more about the BPP and its legacy, Harmachis recommends Lee Lew-Lee’s documentary, “All Power to the People,” which is available for free on Youtube. For additional educational resources about Black oppression and history, the panel members suggest the following: zinnedproject.org, rethinkingschools.org, abolitionistteachingnetwork.org, freedomarchives.org and the Schomburg Library for Research and Black Culture.